75% of severe mental illness

emerges before the age of 25

Over 75% of mental health issues begin before the age of 25.

With suicide continuing to cause the largest loss of life in young people in Australia, mental health support is more important than ever. The Victorian Government has a long-term vision to provide greater access and choice of services for young people living with mental illness. For the young people who are being treated during their experience of mental ill health, we can make their time easier using good design.

Depression, anxiety and behavioural disorders are among the leading causes of illness and disability in young people. But with early intervention – and health care facilities designed to meet their needs – we can help support young people to get the help they need.

Judith Hemsworth is the Principal Design Advisor – Mental Health at the Department of Health. She explains that the needs and preferences of young people experiencing mental ill health can differ greatly according to their age, gender identity, social and cultural background, history of trauma and a host of other factors. The settings in which mental health and wellbeing services for young people are provided must allow for this variability.

emerges before the age of 25

young people experience depression or anxiety at some time

to suicide in young people in 2019

can provide vital support

Psychological distress in young people relates to their overall level of psychological strain or pain. It manifests in psychological states such as depression and anxiety. Levels of psychological distress are higher in young women.

Mental illnesses are diagnosable health conditions. They are health problems that affect how a young person feels, thinks, behaves and interacts with other people. They vary in severity and duration but most mental disorders can be treated, especially if treated early.

Poor mental health can lead to thinking about suicide, making suicide plans, and later to suicide attempts. These can lead to admission to hospital for specialised mental health care. Deaths due to suicide are higher in young men than in young women.

Young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people can face extra obstacles to good mental health. The effects of inter-generational trauma, racism and prejudice, and socioeconomic disadvantage are all relevant in understanding their experiences.

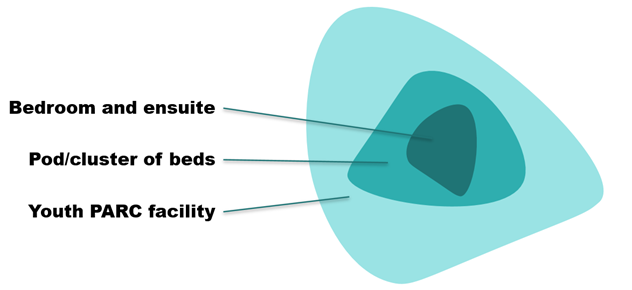

Judith Hemsworth, Principal Advisor Design – Mental Health, Department of Health‘Architects and designers use a number of techniques to accommodate differences. In bed-based services for example, everyone is provided with their own bedroom and dedicated ensuite that they can lock. This is their personal space that they control and which helps them to feel and be safe.’

The mental health service system is intentionally moving away from the use of seclusion and restraint, recognising their harmful aspects. To support this shift, settings for the provision of treatment and support for young people are designed to support them when they struggle with strong emotions.

The types of mental health facilities we design and build include:

Judith Hemsworth explains that the contemporary design approach begins with the creation of a ‘beneficial physical environment’. This incorporates positive features such as:

Bedrooms are grouped in small clusters, with a quiet lounge attached to each. This enables a young person to socialise with a small group of others with similar support needs to themselves.

Judith Hemsworth, Principal Design Advisor – Mental Health, Department of Health‘All clusters share a central kitchen, dining and living space where all of the young people in the facility can come together for meals, discussions or relaxing. A number of spaces for therapeutic and recreational activities are also shared by all.’

Clustered floorplans

The layout for a youth prevention and recovery care (YPARC) facility provides single bedrooms with dedicated ensuites typically clustered into several smaller ‘pods’ with their own sub-lounge space to create a more residential scale and feel.

This arrangement of spaces supports young people by providing them with options regarding the level of social interaction they feel able to engage in at any time.

Designers and architects have to make sure that the interior of the building can easily flex to meet the physical, social and emotional needs of young people that may change, even daily. For example, a bedroom and its ensuite may be able to belong to either of two-clusters of bedrooms clusters by the opening and closing of a door on a corridor. This means that services don’t have to turn someone away because they don’t have enough beds in a bedroom cluster appropriate to support the needs of that young person at that time.

Judith Hemsworth, Principal Design Advisor – Mental Health, Department of Health‘The beneficial background is further enhanced by the provision of newer spaces such as sensory rooms and high needs rooms. These spaces are designed and fitted out with features and equipment that the young person may use when they are struggling with strong emotions. What one person finds calming and reassuring may differ greatly from what another person prefers, so these spaces are provided with a selection of options. For example, audio-visual displays that can be modified to suit individual taste, large bean bags and weighted blankets for cocooning in, music systems, aromatherapy, rocking chairs and more.’

When designing a mental health facility, it’s important to consider the needs of the people we are designing for. Who better to inform the design than those with lived experience of mental ill health?

That’s where co-design comes into play.

Co-design is about involving people with lived experience in the design process. It means including their input in a meaningful way as equal partners so that the results of the design meet their needs. Co-design grew out of the Scandinavian participatory design movement in the 1970s and has two underlying ideas. The first is that everyone should have the right to participate in the decisions that impact on their life. The second is that everyone has valuable knowledge to contribute to a design process.

Judith Hemsworth, Principal Design Advisor – Mental Health, Department of Health‘The voice of those with lived experience is needed to challenge existing paradigms so the new facilities reflect new social relationships and new ways of providing services rather than replicating old patterns.’

Think about designing a youth mental health facility. We want it to feel safe and welcoming to the young people who will use it. Imagine we’ve painted the interiors with bright colours and put bean bags everywhere because ‘that’s what young people like.’ Rather than relying on stereotypes, wouldn’t it be better to consult young people themselves, and in particular young people who have lived experience of mental ill health? By using co-design, we incorporate multiple perspectives into the design process. We can centre the lived experience of young people to not only identify the issues they face but to inform the design solutions as well.

When we talk about co-design we’re designing with young people, rather than for them.

As Judith Hemsworth explains, facilities that were designed 30 or 40 years ago are seen by young people as institutional, unsafe and unattractive rather than places that will empower and support them in their treatment and recovery. ‘It is critical that young voices are heard as equal partners in shaping the physical settings that house the services they have also co-designed. This will help ensure that these settings appear attractive and non-stigmatising to young people, encouraging and inviting them to engage with the services on offer and supporting them in that.’

Co-design of mental health facilities involves more than just having a one-off workshop. It’s an approach that benefits from involving multiple young people, at multiple touchpoints throughout the design process, using a mix of face-to-face and online methods, like focus groups, workshops, online surveys and webchats.

The co-design process works best when it’s as inclusive as possible, involving young people who have a diverse mix of experiences and backgrounds. This could include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people, young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, LGBTIQA+, young people with experience of juvenile justice and young people who are disengaged from school or work.

Michael Walker, Principal Advisor, Universal Design, VHBA‘We need to have a better sense of co-creation. And if we get a better sense of co-creation, all the people that use these spaces have got a hand on the steering wheel of design.’

Artist’s impression of the shared kitchen and dining areas at the North West Metropolitan YPARC

Bringing nature into our building designs has been shown to have a positive effect on wellbeing. But it’s more than bringing some pot plants into a room. Biophilic design recognises that patterns, materials, sounds, smells and light can all contribute to feeling good. We can elevate the moods of the young people who use our mental health facilities by blurring the division between inside and outside, bringing nature in by using plants as well as natural patterns and materials.

We know that exposure to natural light can help with mood and promote happiness. Views of nature have also been shown to reduce stress. Even small amounts of time spent in nature can improve our mental and physical wellbeing. Spending time in a garden can elevate our mood and reduce stress.

It is important for young people to have the therapeutic benefits that access to external spaces provides. As such, we incorporate various design elements that enable people to have access to external areas on each level of a building wherever possible.

Judith Hemsworth, Principal Design Advisor – Mental Health, Department of Health‘Above ground floor level we might wrap rooms around a central courtyard that is open to the sky or provide a semi-enclosed balcony or “winter garden”. Other approaches include planting trees close to the building at ground floor level so that the canopies can be viewed from upper levels of the building.

Even when working at ground floor level, there are situations where it may not be possible to have larger plants and trees in an outdoor space. We then try to provide a “borrowed landscape” with trees and heavy planting on the other side of a tall fence or screen where these are needed.’

A curving, organically-shaped walkway within the Orygen and OYH Poplar Road precinct redevelopment in Parkville

As part of the Victorian Government’s response to the Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System, we’re designing and delivering contemporary, safe and high-quality mental health facilities across Victoria.

The award-winning Orygen and OYH Poplar Road precinct redevelopment is a clinical and research centre for young people with serious mental illness. The design involved input from more than 140 young people to ensure young voices were heard. They contributed ideas on furniture, the design of consulting rooms, living and resting spaces, and even on the design of the bathrooms. The result was a space that feels inclusive and safe.

The building was designed to reflect the natural beauty of the surrounding landscape. Natural, laminated timbers and curved, irregular shapes were used throughout. The consulting rooms have access to outside decks so young people have space to debrief, settle and reflect. Young people can access clinical services in a comfortable and safe environment, designed to meet their needs.

Learn more about the Orygen and OYH Poplar Road precinct redevelopment on our dedicated project page.

In 2020, we completed a $6.2 million upgrade of the intensive care area at Orygen Youth Health in Footscray.

Orygen Youth Health provides specialist mental health services for young people aged 15-25.

The upgrade included four new inpatient beds and enhanced living, private and treatment spaces. The intensive care area will help Orygen Youth Health provide safe and appropriate clinical treatment options for acute mental illness and ensure young people can access treatment and care close to home and support networks.

Learn more about the Orygen Youth Health intensive care area upgrade via our dedicated project page.

The Victorian Government has invested $141 million to deliver five new and refurbish the three existing youth prevention and recovery care (YPARC) facilities across the state.

YPARC facilities provide residential short and medium-term treatment and support for young people aged between 16-25, who are living with, or diagnosed with, mental ill health.

The new facilities are being co-designed to create a welcoming, safe and therapeutic environment with private bedrooms complete with ensuite bathrooms. Communal kitchens, dining and living areas, activity areas and outdoor garden areas will provide space for leisure, recreational activities, therapeutic and skill development activities and family visits.

Young people with lived experience of mental ill health, their families, carers and mental health professionals are all engaged in the co-design of these new facilities.

This project is part of the urgent response to recommendations from the Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System.

Learn more about the Youth prevention and recovery care centre expansion program via our dedicated program page.

The Victorian Government is investing $11.9 million in the new North West Metropolitan Youth Prevention and Recovery Care (YPARC) centre.

The 20-bed facility will provide short and medium-term treatment and support in a residential setting for young people aged 16-25 experiencing mental ill health in Melbourne’s West.

The centre will offer a safe and supportive environment for young people who may find it difficult to cope at home. The service will help young people suffering mental illness who could benefit from treatment and support in a short to medium-term residential stay.

This facility was designed to create a welcoming and therapeutic environment while keeping young people safe.

Young people with lived experience of mental ill health, their families, carers and mental health professionals are all engaged in the co-design of this facility.

Learn more about the North West Metropolitan YPARC centre via our dedicated project page.

The Victorian Government is investing $7.3 million to deliver the Statewide Child and Family Centre in Melbourne’s north.

The Victorian-first centre will improve access to mental health services for children up to 11 years of age in a safe and supportive residential setting.

The centre will provide therapy for children and families who have experienced negative or traumatic events and continue to have challenges with relationships and connections.

Staffed 24 hours a day, seven days a week, the new 12-bed facility will allow children and their families to stay onsite while they receive flexible, family-centred therapy and support from child and family mental health specialists.

Learn more about the Statewide Child and Family Centre via our dedicated project page.

Homes Victoria and the Department of Health are working in partnership to design 500 new medium-term supported housing places for young people. Supported housing means housing that is accompanied by integrated and tailored mental health and wellbeing supports.

The places are designed for young people aged between 18 and 25 who are living with mental illness and experiencing unstable housing or homelessness. Young people will be able to receive support in these housing places for up to two years.

Co-design is a critical part of ensuring that the supported housing reforms improve the outcomes for people living with mental illness. This includes involving people with lived experience of mental illness and unstable housing or homelessness as well as families, carers and supporters. A dedicated co-design process with young people aged between 18 and 25 will be run in mid-2022. The co-design will help inform the design of the supported housing places, including wellbeing supports.

Learn more about supported housing on the Victorian Government website.

Mental health helplines can provide support if you or someone you know is experiencing mental ill health:

A comprehensive list of counselling, online and phone supports for mental illness is available on the Better Health Channel website.

The Department of Health also provides information on mental health resources for those struggling due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. They are available on the Mental health resources page on the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Victoria website

Stay up-to-date on our announcements and projects by signing up to our online newsletters.

17 March 2022

31 July 2019

18 November 2020

07 August 2023